DAOs are not corporations: where decentralization in autonomous organizations matters

2022 Sep 20See all posts

Special thanks to Karl Floersch and Tina Zhen for feedback and review on earlier versions of this article.

Recently, there has been a lot of discourse around the idea that highly decentralized DAOs do not work, and DAO governance should start to more closely resemble that of traditional corporations in order to remain competitive. The argument is always similar: highly decentralized governance is inefficient, and traditional corporate governance structures with boards, CEOs and the like evolved over hundreds of years to optimize for the goal of making good decisions and delivering value to shareholders in a changing world. DAO idealists are naive to assume that egalitarian ideals of decentralization can outperform this, when attempts to do this in the traditional corporate sector have had marginal success at best.

This post will argue why this position is often wrong, and offer a different and more detailed perspective about where different kinds of decentralization are important. In particular, I will focus on three types of situations where decentralization is important:

- Decentralization for making better decisions in concave environments, where pluralism and even naive forms of compromise are on average likely to outperform the kinds of coherency and focus that come from centralization.

- Decentralization for censorship resistance: applications that need to continue functioning while resisting attacks from powerful external actors.

- Decentralization as credible fairness: applications where DAOs are taking on nation-state-like functions like basic infrastructure provision, and so traits like predictability, robustness and neutrality are valued above efficiency.

Centralization is convex, decentralization is concave

See the original post: https://vitalik.ca/general/2020/11/08/concave.html

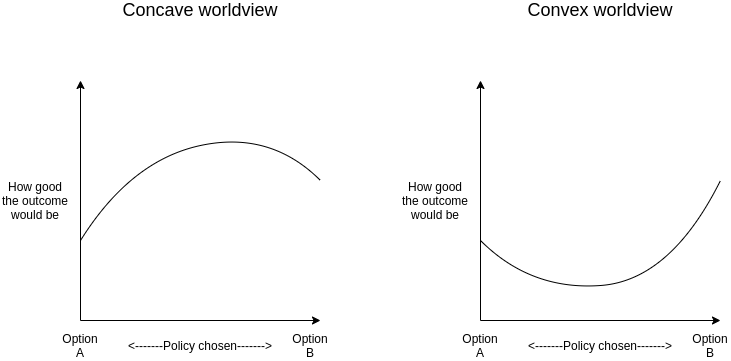

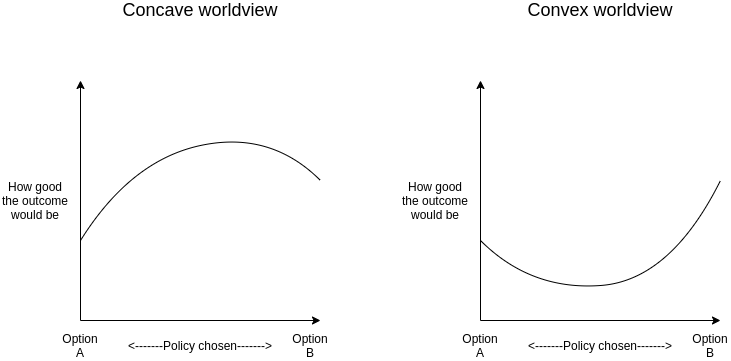

One way to categorize decisions that need to be made is to look at whether they are convex or concave. In a choice between A and B, we would first look not at the question of A vs B itself, but instead at a higher-order question: would you rather take a compromise between A and B or a coin flip? In expected utility terms, we can express this distinction using a graph:

If a decision is concave, we would prefer a compromise, and if it's convex, we would prefer a coin flip. Often, we can answer the higher-order question of whether a compromise or a coin flip is better much more easily than we can answer the first-order question of A vs B itself.

Examples of convex decisions include:

- Pandemic response: a 100% travel ban may work at keeping a virus out, a 0% travel ban won't stop viruses but at least doesn't inconvenience people, but a 50% or 90% travel ban is the worst of both worlds.

- Military strategy: attacking on front A may make sense, attacking on front B may make sense, but splitting your army in half and attacking at both just means the enemy can easily deal with the two halves one by one

- Technology choices in crypto protocols: using technology A may make sense, using technology B may make sense, but some hybrid between the two often just leads to needless complexity and even adds risks of the two interfering with each other.

Examples of concave decisions include:

- Judicial decisions: an average between two independently chosen judgements is probably more likely to be fair, and less likely to be completely ridiculous, than a random choice of one of the two judgements.

- Public goods funding: usually, giving $X to each of two promising projects is more effective than giving $2X to one and nothing to the other. Having any money at all gives a much bigger boost to a project's ability to achieve its mission than going from $X to $2X does.

- Tax rates: because of quadratic deadweight loss mechanics, a tax rate of X% is often only a quarter as harmful as a tax rate of 2X%, and at the same time more than half as good at raising revenue. Hence, moderate taxes are better than a coin flip between low/no taxes and high taxes.

When decisions are convex, decentralizing the process of making that decision can easily lead to confusion and low-quality compromises. When decisions are concave, on the other hand, relying on the wisdom of the crowds can give better answers. In these cases, DAO-like structures with large amounts of diverse input going into decision-making can make a lot of sense. And indeed, people who see the world as a more concave place in general are more likely to see a need for decentralization in a wider variety of contexts.

Should VitaDAO and Ukraine DAO be DAOs?

Many of the more recent DAOs differ from earlier DAOs, like MakerDAO, in that whereas the earlier DAOs are organized around providing infrastructure, the newer DAOs are organized around performing various tasks around a particular theme. VitaDAO is a DAO funding early-stage longevity research, and UkraineDAO is a DAO organizing and funding efforts related to helping Ukrainian victims of war and supporting the Ukrainian defense effort. Does it make sense for these to be DAOs?

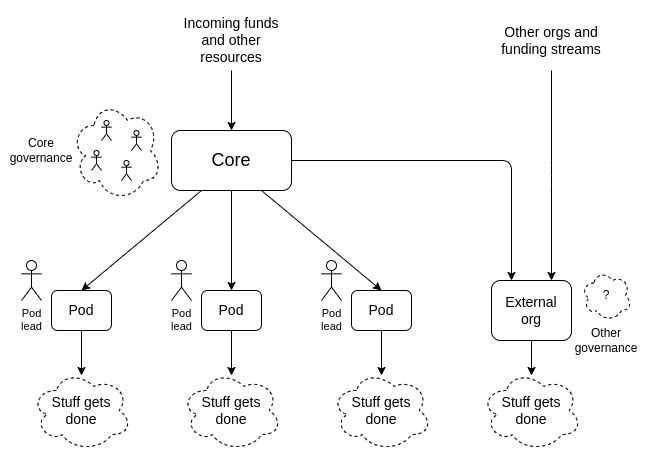

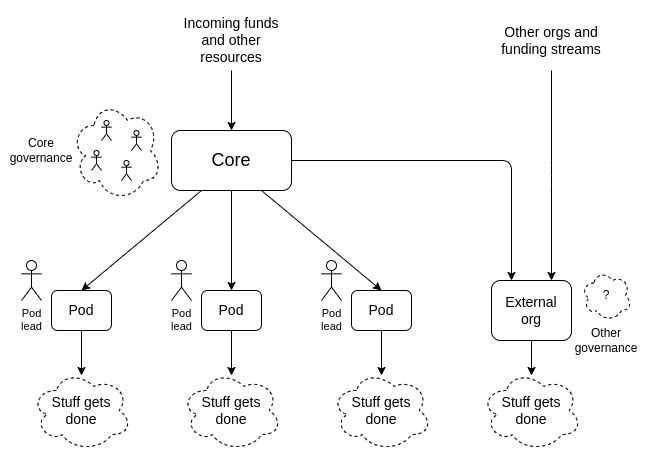

This is a nuanced question, and we can get a view of one possible answer by understanding the internal workings of UkraineDAO itself. Typical DAOs tend to "decentralize" by gathering large amounts of capital into a single pool and using token-holder voting to fund each allocation. UkraineDAO, on the other hand, works by splitting its functions up into many pods, where each pod works as independently as possible. A top layer of governance can create new pods (in principle, governance can also fund pods, though so far funding has only gone to external Ukraine-related organizations), but once a pod is made and endowed with resources, it functions largely on its own. Internally, individual pods do have leaders and function in a more centralized way, though they still try to respect an ethos of personal autonomy.

One natural question that one might ask is: isn't this kind of "DAO" just rebranding the traditional concept of multi-layer hierarchy? I would say this depends on the implementation: it's certainly possible to take this template and turn it into something that feels authoritarian in the same way stereotypical large corporations do, but it's also possible to use the template in a very different way.

Two things that can help ensure that an organization built this way will actually turn out to be meaningfully decentralized include:

- A truly high level of autonomy for pods, where the pods accept resources from the core and are occasionally checked for alignment and competence if they want to keep getting those resources, but otherwise act entirely on their own and don't "take orders" from the core.

- Highly decentralized and diverse core governance. This does not require a "governance token", but it does require broader and more diverse participation in the core. Normally, broad and diverse participation is a large tax on efficiency. But if (1) is satisfied, so pods are highly autonomous and the core needs to make fewer decisions, the effects of top-level governance being less efficient become smaller.

Now, how does this fit into the "convex vs concave" framework? Here, the answer is roughly as follows: the (more decentralized) top level is concave, the (more centralized within each pod) bottom level is convex. Giving a pod $X is generally better than a coin flip between giving it $0 and giving it $2X, and there isn't a large loss from having compromises or "inconsistent" philosophies guiding different decisions. But within each individual pod, having a clear opinionated perspective guiding decisions and being able to insist on many choices that have synergies with each other is much more important.

Decentralization and censorship resistance

The most often publicly cited reason for decentralization in crypto is censorship resistance: a DAO or protocol needs to be able to function and defend itself despite external attack, including from large corporate or even state actors. This has already been publicly talked about at length, and so deserves less elaboration, but there are still some important nuances.

Two of the most successful censorship-resistant services that large numbers of people use today are The Pirate Bay and Sci-Hub. The Pirate Bay is a hybrid system: it's a search engine for BitTorrent, which is a highly decentralized network, but the search engine itself is centralized. It has a small core team that is dedicated to keeping it running, and it defends itself with the mole's strategy in whack-a-mole: when the hammer comes down, move out of the way and re-appear somewhere else. The Pirate Bay and Sci-Hub have both frequently changed domain names, relied on arbitrage between different jurisdictions, and used all kinds of other techniques. This strategy is centralized, but it has allowed them both to be successful both at defense and at product-improvement agility.

DAOs do not act like The Pirate Bay and Sci-Hub; DAOs act like BitTorrent. And there is a reason why BitTorrent does need to be decentralized: it requires not just censorship resistance, but also long-term investment and reliability. If BitTorrent got shut down once a year and required all its seeders and users to switch to a new provider, the network would quickly degrade in quality. Censorship resistance-demanding DAOs should also be in the same category: they should be providing a service that isn't just evading permanent censorship, but also evading mere instability and disruption. MakerDAO (and the Reflexer DAO which manages RAI) are excellent examples of this. A DAO running a decentralized search engine probably does not: you can just build a regular search engine and use Sci-Hub-style techniques to ensure its survival.

Decentralization as credible fairness

Sometimes, DAOs' primary concern is not a need to resist nation states, but rather a need to take on some of the functions of nation states. This often involves tasks that can be described as "maintaining basic infrastructure". Because governments have less ability to oversee DAOs, DAOs need to be structured to take on a greater ability to oversee themselves. And this requires decentralization.

Of course, it's not actually possible to come anywhere close to eliminating hierarchy and inequality of information and decision-making power in its entirety etc etc etc, but what if we can get even 30% of the way there?

Consider three motivating examples: algorithmic stablecoins, the Kleros court, and the Optimism retroactive funding mechanism.

- An algorithmic stablecoin DAO is a system that uses on-chain financial contracts to create a crypto-asset whose price tracks some stable index, often but not necessarily the US dollar.

- Kleros is a "decentralized court": a DAO whose function is to give rulings on arbitration questions such as "is this Github commit an acceptable submission to this on-chain bounty?"

- Optimism's retroactive funding mechanism is a component of the Optimism DAO which retroactively rewards projects that have provided value to the Ethereum and Optimism ecosystems.

In all three cases, there is a need to make subjective judgements, which cannot be done automatically through a piece of on-chain code. In the first case, the goal is simply to get reasonably accurate measurements of some price index. If the stablecoin tracks the US dollar, then you just need the ETH/USD price. If hyperinflation or some other reason to abandon the US dollar arises, the stablecoin DAO might need to manage a trustworthy on-chain CPI calculation. Kleros is all about making unavoidably subjective judgements on any arbitrary question that is submitted to it, including whether or not submitted questions should be rejected for being "unethical". Optimism's retroactive funding is tasked with one of the most open-ended subjective questions at all: what projects have done work that is the most useful to the Ethereum and Optimism ecosystems?

All three cases have an unavoidable need for "governance", and pretty robust governance too. In all cases, governance being attackable, from the outside or the inside, can easily lead to very big problems. Finally, the governance doesn't just need to be robust, it needs to credibly convince a large and untrusting public that it is robust.

The algorithmic stablecoin's Achilles heel: the oracle

Algorithmic stablecoins depend on oracles. In order for an on-chain smart contract to know whether to target the value of DAI to 0.005 ETH or 0.0005 ETH, it needs some mechanism to learn the (external-to-the-chain) piece of information of what the ETH/USD price is. And in fact, this "oracle" is the primary place at which an algorithmic stablecoin can be attacked.

This leads to a security conundrum: an algorithmic stablecoin cannot safely hold more collateral, and therefore cannot issue more units, than the market cap of its speculative token (eg. MKR, FLX...), because if it does, then it becomes profitable to buy up half the speculative token sipply, use those tokens to control the oracle, and steal funds from users by feeding bad oracle values and liquidating them.

Here is a possible alternative design for a stablecoin oracle: add a layer of indirection. Quoting the ethresear.ch post:

We set up a contract where there are 13 "providers"; the answer to a query is the median of the answer returned by these providers. Every week, there is a vote, where the oracle token holders can replace one of the providers ...

The security model is simple: if you trust the voting mechanism, you can trust the oracle output, unless 7 providers get corrupted at the same time. If you trust the current set of oracle providers, you can trust the output for at least the next six weeks, even if you completely do not trust the voting mechanism. Hence, if the voting mechanism gets corrupted, there will be able time for participants in any applications that depend on the oracle to make an orderly exit.

Notice the very un-corporate-like nature of this proposal. It involves taking away the governance's ability to act quickly, and intentionally spreading out oracle responsibility across a large number of participants. This is valuable for two reasons. First, it makes it harder for outsiders to attack the oracle, and for new coin holders to quickly take over control of the oracle. Second, it makes it harder for the oracle participants themselves to collude to attack the system. It also mitigates oracle extractable value, where a single provider might intentionally delay publishing to personally profit from a liquidation (in a multi-provider system, if one provider doesn't immediately publish, others soon will).

Fairness in Kleros

The "decentralized court" system Kleros is a really valuable and important piece of infrastructure for the Ethereum ecosystem: Proof of Humanity uses it, various "smart contract bug insurance" products use it, and many other projects plug into it as some kind of "adjudication of last resort".

Recently, there have been some public concerns about whether or not the platform's decision-making is fair. Some participants have made cases, trying to claim a payout from decentralized smart contract insurance platforms that they argue they deserve. Perhaps the most famous of these cases is Mizu's report on case #1170. The case blew up from being a minor language intepretation dispute into a broader scandal because of the accusation that insiders to Kleros itself were making a coordinated effort to throw a large number of tokens to pushing the decision in the direction they wanted. A participant to the debate writes:

The incentives-based decision-making process of the court ... is by all appearances being corrupted by a single dev with a very large (25%) stake in the courts.

Of course, this is but one side of one issue in a broader debate, and it's up to the Kleros community to figure out who is right or wrong and how to respond. But zooming out from the question of this individual case, what is important here is the the extent to which the entire value proposition of something like Kleros depends on it being able to convince the public that it is strongly protected against this kind of centralized manipulation. For something like Kleros to be trusted, it seems necessary that there should not be a single individual with a 25% stake in a high-level court. Whether through a more widely distributed token supply, or through more use of non-token-driven governance, a more credibly decentralized form of governance could help Kleros avoid such concerns entirely.

Optimism retro funding

Optimism's retroactive founding round 1 results were chosen by a quadratic vote among 24 "badge holders". Round 2 will likely use a larger number of badge holders, and the eventual goal is to move to a system where a much larger body of citizens control retro funding allocation, likely through some multilayered mechanism involving sortition, subcommittees and/or delegation.

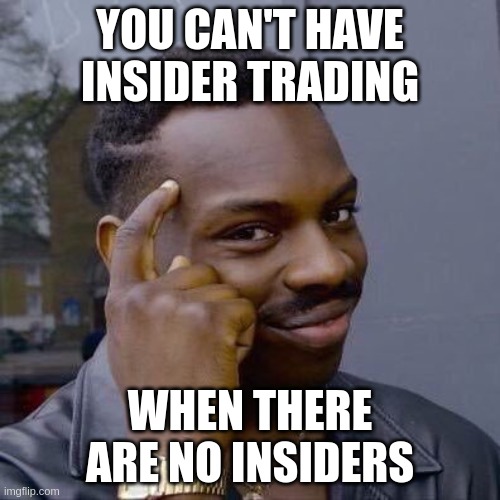

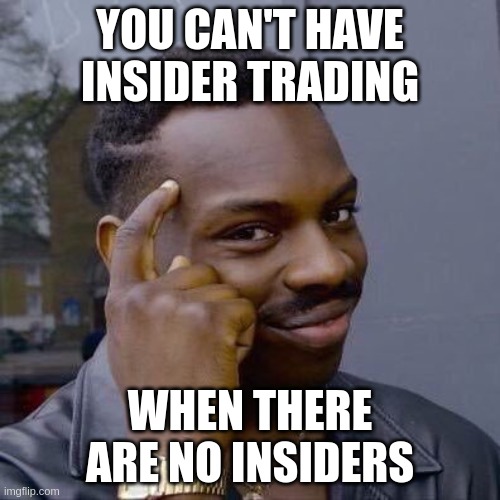

There have been some internal debates about whether to have more vs fewer citizens: should "citizen" really mean something closer to "senator", an expert contributor who deeply understands the Optimism ecosystem, should it be a position given out to just about anyone who has significantly participated in the Optimism ecosystem, or somewhere in between? My personal stance on this issue has always been in the direction of more citizens, solving governance inefficiency issues with second-layer delegation instead of adding enshrined centralization into the governance protocol. One key reason for my position is the potential for insider trading and self-dealing issues.

The Optimism retroactive funding mechanism has always been intended to be coupled with a prospective speculation ecosystem: public-goods projects that need funding now could sell "project tokens", and anyone who buys project tokens becomes eligible for a large retroactively-funded compensation later. But this mechanism working well depends crucially on the retroactive funding part working correctly, and is very vulnerable to the retroactive funding mechanism becoming corrupted. Some example attacks:

- If some group of people has decided how they will vote on some project, they can buy up (or if overpriced, short) its project token ahead of releasing the decision.

- If some group of people knows that they will later adjudicate on some specific project, they can buy up the project token early and then intentionally vote in its favor even if the project does not actually deserve funding.

- Funding deciders can accept bribes from projects.

There are typically three ways of dealing with these types of corruption and insider trading issues:

- Retroactively punish malicious deciders.

- Proactively filter for higher-quality deciders.

- Add more deciders.

The corporate world typically focuses on the first two, using financial surveillance and judicious penalties for the first and in-person interviews and background checks for the second. The decentralized world has less access to such tools: project tokens are likely to be tradeable anonymously, DAOs have at best limited recourse to external judicial systems, and the remote and online nature of the projects and the desire for global inclusivity makes it harder to do background checks and informal in-person "smell tests" for character. Hence, the decentralized world needs to put more weight on the third technique: distribute decision-making power among more deciders, so that each individual decider has less power, and so collusions are more likely to be whistleblown on and revealed.

Should DAOs learn more from corporate governance or political science?

Curtis Yarvin, an American philosopher whose primary "big idea" is that corporations are much more effective and optimized than governments and so we should improve governments by making them look more like corporations (eg. by moving away from democracy and closer to monarchy), recently wrote an article expressing his thoughts on how DAO governance should be designed. Not surprisingly, his answer involves borrowing ideas from governance of traditional corporations. From his introduction:

Instead the basic design of the Anglo-American limited-liability joint-stock company has remained roughly unchanged since the start of the Industrial Revolution—which, a contrarian historian might argue, might actually have been a Corporate Revolution. If the joint-stock design is not perfectly optimal, we can expect it to be nearly optimal.

While there is a categorical difference between these two types of organizations—we could call them first-order (sovereign) and second-order (contractual) organizations—it seems that society in the current year has very effective second-order organizations, but not very effective first-order organizations.

Therefore, we probably know more about second-order organizations. So, when designing a DAO, we should start from corporate governance, not political science.

Yarvin's post is very correct in identifying the key difference between "first-order" (sovereign) and "second-order" (contractual) organizations - in fact, that exact distinction is precisely the topic of the section in my own post above on credible fairness. However, Yarvin's post makes a big, and surprising, mistake immediately after, by immediately pivoting to saying that corporate governance is the better starting point for how DAOs should operate. The mistake is surprising because the logic of the situation seems to almost directly imply the exact opposite conclusion. Because DAOs do not have a sovereign above them, and are often explicitly in the business of providing services (like currency and arbitration) that are typically reserved for sovereigns, it is precisely the design of sovereigns (political science), and not the design of corporate governance, that DAOs have more to learn from.

To Yarvin's credit, the second part of his post does advocate an "hourglass" model that combines a decentralized alignment and accountability layer and a centralized management and execution layer, but this is already an admission that DAO design needs to learn at least as much from first-order orgs as from second-order orgs.

Sovereigns are inefficient and corporations are efficient for the same reason why number theory can prove very many things but abstract group theory can prove much fewer things: corporations fail less and accomplish more because they can make more assumptions and have more powerful tools to work with. Corporations can count on their local sovereign to stand up to defend them if the need arises, as well as to provide an external legal system they can lean on to stabilize their incentive structure. In a sovereign, on the other hand, the biggest challenge is often what to do when the incentive structure is under attack and/or at risk of collapsing entirely, with no external leviathan standing ready to support it.

Perhaps the greatest problem in the design of successful governance systems for sovereigns is what Samo Burja calls "the succession problem": how to ensure continuity as the system transitions from being run by one group of humans to another group as the first group retires. Corporations, Burja writes, often just don't solve the problem at all:

Silicon Valley enthuses over "disruption" because we have become so used to the succession problem remaining unsolved within discrete institutions such as companies.

DAOs will need to solve the succession problem eventually (in fact, given the sheer frequency of the "get rich and retire" pattern among crypto early adopters, some DAOs have to deal with succession issues already). Monarchies and corporate-like forms often have a hard time solving the succession problem, because the institutional structure gets deeply tied up with the habits of one specific person, and it either proves difficult to hand off, or there is a very-high-stakes struggle over whom to hand it off to. More decentralized political forms like democracy have at least a theory of how smooth transitions can happen. Hence, I would argue that for this reason too, DAOs have more to learn from the more liberal and democratic schools of political science than they do from the governance of corporations.

Of course, DAOs will in some cases have to accomplish specific complicated tasks, and some use of corporate-like forms for accomplishing those tasks may well be a good idea. Additionally, DAOs need to handle unexpected uncertainty. A system that was intended to function in a stable and unchanging way around one set of assumptions, when faced with an extreme and unexpected change to those circumstances, does need some kind of brave leader to coordinate a response. A prototypical example of the latter is stablecoins handling a US dollar collapse: what happens when a stablecoin DAO that evolved around the assumption that it's just trying to track the US dollar suddenly faces a world where the US dollar is no longer a viable thing to be tracking, and a rapid switch to some kind of CPI is needed?

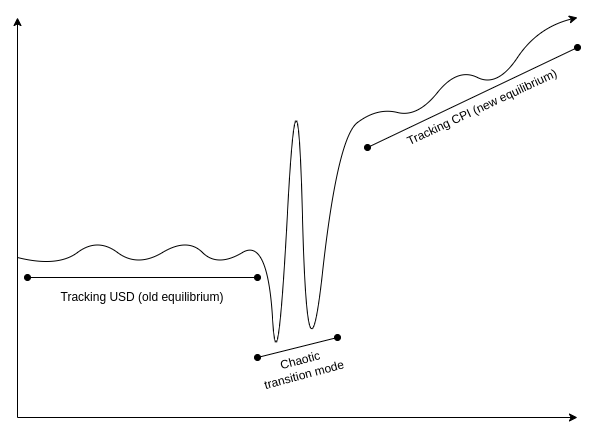

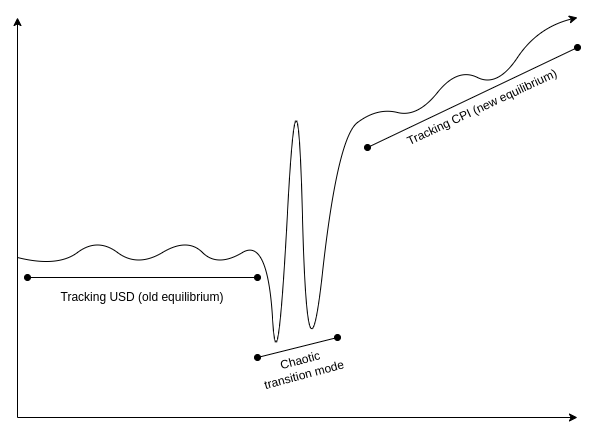

Stylized diagram of the internal experience of the RAI ecosystem going through an unexpected transition to a CPI-based regime if the USD ceases to be a viable reference asset.

Here, corporate governance-inspired approaches may seem better, because they offer a ready-made pattern for responding to such a problem: the founder organizes a pivot. But as it turns out, the history of political systems also offers a pattern well-suited to this situation, and one that covers the question of how to go back to a decentralized mode when the crisis is over: the Roman Republic custom of electing a dictator for a temporary term to respond to a crisis.

Realistically, we probably only need a small number of DAOs that look more like constructs from political science than something out of corporate governance. But those are the really important ones. A stablecoin does not need to be efficient; it must first and foremost be stable and decentralized. A decentralized court is similar. A system that directs funding for a particular cause - whether Optimism retroactive funding, VitaDAO, UkraineDAO or something else - is optimizing for a much more complicated purpose than profit maximization, and so an alignment solution other than shareholder profit is needed to make sure it keeps using the funds for the purpose that was intended.

By far the greatest number of organizations, even in a crypto world, are going to be "contractual" second-order organizations that ultimately lean on these first-order giants for support, and for these organizations, much simpler and leader-driven forms of governance emphasizing agility are often going to make sense. But this should not distract from the fact that the ecosystem would not survive without some non-corporate decentralized forms keeping the whole thing stable.

DAO不是公司:自治组织中的权力下放很重要

2022 9月 20查看所有帖子

特别感谢卡尔·弗洛尔施和蒂娜·甄对本文早期版本的反馈和评论。

最近,围绕高度去中心化的DAO不起作用的想法有很多讨论,DAO治理应该开始更类似于传统公司的治理,以保持竞争力。论点总是相似的:高度分散的治理效率低下,传统的公司治理结构,包括董事会、首席执行官等,经过数百年的演变,以实现在不断变化的世界中做出良好决策和为股东创造价值的目标。DAO的理想主义者天真地认为,平等主义的去中心化理想可以超越这一点,而在传统企业部门这样做的尝试充其量只是取得了微不足道的成功。

这篇文章将论证为什么这个立场往往是错误的,并提供了一个不同和更详细的观点,说明不同类型的权力下放在哪里是重要的。特别是,我将重点介绍权力下放很重要的三种情况:

- 在凹陷的环境中做出更好决策的权力下放,在这种环境中,多元化甚至天真的妥协形式平均可能胜过集中化带来的连贯性和专注力。

- 用于抗审查的去中心化:需要继续运行的应用程序,同时抵御来自强大外部参与者的攻击。

- 作为可信公平性的去中心化:DAO承担类似民族国家功能的应用程序,如基础设施的提供,因此可预测性、健壮性和中立性等特征的价值高于效率。

集中化是凸的,分散是凹的

查看原始帖子: https://vitalik.ca/general/2020/11/08/concave.html

对需要做出的决策进行分类的一种方法是查看它们是凸的还是凹的。在A和B之间进行选择时,我们首先不会看A与B本身的问题,而是看一个更高阶的问题:你宁愿在A和B之间做出妥协还是掷硬币?在预期的效用术语中,我们可以用一个图来表达这种区别:

如果一个决定是凹陷的,我们宁愿妥协,如果它是凸的,我们更喜欢掷硬币。通常,我们可以回答高阶问题,即妥协还是掷硬币比回答A与B本身的一阶问题要容易得多。

凸决策的示例包括:

- 大流行应对:100%的旅行禁令可能有助于阻止病毒,0%的旅行禁令不会阻止病毒,但至少不会给人们带来不便,但50%或90%的旅行禁令是两个世界中最糟糕的。

- 军事战略:在前线A进攻可能有意义,在前线B进攻可能有意义,但是将你的军队一分为二,同时攻击两者只是意味着敌人可以很容易地一个接一个地对付两半

- 加密协议中的技术选择:使用技术A可能有意义,使用技术B可能有意义,但两者之间的某种混合通常只会导致不必要的复杂性,甚至增加两者相互干扰的风险。

凹陷决策的示例包括:

- 司法判决:与随机选择两个判决中的一个相比,两个独立选择的判决之间的平均值可能更有可能是公平的,而不太可能是完全荒谬的。

- 公共产品融资:通常,给两个有前途的项目中的每一个提供$X比给一个项目2倍而向另一个项目什么都不给更有效。与从$X美元增加到2倍相比,拥有任何资金都会对项目实现其任务的能力产生更大的推动力。

- 税率:由于二次自重损失机制,X%的税率通常只有2X%税率的四分之一,同时在提高收入方面也好一半以上。因此,适度的税收比在低/无税收和高税收之间翻转硬币要好。

当决策是凸起的,分散决策的过程很容易导致混乱和低质量的妥协。另一方面,当决策是凹陷的,依靠人群的智慧可以给出更好的答案。在这些情况下,具有大量不同投入的DAO结构可以非常有意义。事实上,那些将世界视为一个更凹陷的地方的人更有可能在更广泛的背景下看到权力下放的必要性。

维达澳和乌克兰道奥应该是道琼斯吗?

许多较新的DAO与早期的DAO(如MakerDAO)的不同之处在于,早期的DAO是围绕提供基础设施组织的,而较新的DAO则围绕围绕特定主题执行各种任务进行组织。VitaDAO是DAO资助的早期长寿研究,乌克兰DAO是一个DAO组织和资助与帮助乌克兰战争受害者和支持乌克兰国防努力相关的工作。这些作为DAO有意义吗?

这是一个微妙的问题,我们可以通过了解乌克兰DAO本身的内部运作来获得一个可能的答案。典型的DAO倾向于通过将大量资金聚集到单个池中并使用代币持有者投票来为每个分配提供资金来“分散”。另一方面,乌克兰DAO的工作原理是将其功能拆分为多个 pod,其中每个 pod 尽可能独立地工作。顶层治理可以创建新的 pod(原则上,治理也可以为 pod 提供资金,尽管到目前为止,资金只流向了与乌克兰相关的外部组织),但是一旦一个 pod 被制造出来并赋予了资源,它在很大程度上就独立运作了。在内部,个人豆荚确实有领导者,并以更集中的方式运作,尽管他们仍然试图尊重个人自主的精神。

人们可能会问的一个自然问题是:这种“DAO”不就是在重塑传统的多层层次结构概念吗?我会说这取决于实现:当然可以采用这个模板并将其变成像刻板大公司一样感到专制的东西,但也可以以非常不同的方式使用模板。

有两件事可以帮助确保以这种方式构建的组织实际上会变得有意义的去中心化,包括:

- 对于 Pod 来说,这是一个真正高度的自治权,Pod 接受来自核心的资源,如果他们想要继续获得这些资源,但除此之外,它们完全靠自己行动,不从核心“接受命令”,则偶尔会检查它们的对齐性和能力。

- 高度分散和多样化的核心治理。这不需要“治理令牌”,但它确实需要更广泛和更多样化的核心参与。通常,广泛而多样化的参与是对效率的一大征税。但是,如果(1)得到满足,那么 pod 是高度自治的,核心需要做出更少的决策,那么顶层治理效率较低的影响就会变小。

现在,这如何适应“凸与凹”框架?在这里,答案大致如下:(更分散的)顶层是凹的,(在每个pod中更集中的)底层是凸的。给一个豆荚$X通常比在给它0美元和给它2倍美元之间掷硬币要好,而且没有妥协或“不一致”的哲学指导不同决策的很大损失。但是,在每个单独的豆荚中,拥有明确的固执己见的观点来指导决策并能够坚持许多彼此具有协同作用的选择更为重要。

权力下放和抵制审查

加密货币中最常被公开引用的去中心化原因是对审查制度的抵制:DAO或协议需要能够在外部攻击(包括来自大型企业甚至国家行为者)的情况下发挥作用并保护自己。这已经公开详细讨论了,因此值得较少阐述,但仍有一些重要的细微差别。

今天很多人使用的两个最成功的抗审查服务是海盗湾和Sci-Hub。海盗湾是一个混合系统:它是BitTorrent的搜索引擎,这是一个高度分散的网络,但搜索引擎本身是集中的。它有一个小型的核心团队,致力于保持它的运行,它用鼹鼠的策略来保护自己:当锤子落下时,移开并在其他地方重新出现。海盗湾和Sci-Hub都经常更改域名,依赖于不同司法管辖区之间的套利,并使用各种其他技术。这种策略是集中的,但它使它们在防御和产品改进敏捷性方面都取得了成功。

DAO不像海盗湾和科学中心那样行事;DAO 的行为就像比特托伦特一样。BitTorrent确实需要去中心化是有原因的:它不仅需要抗审查性,还需要长期投资和可靠性。如果BitTorrent每年关闭一次,并要求所有播种机和用户切换到新的提供商,网络的质量将很快下降。审查抵制要求的DAO也应该属于同一类别:他们应该提供的服务不仅要逃避永久性的审查,还要逃避纯粹的不稳定和破坏。创客道(以及管理RAI的反射器DAO)就是很好的例子。运行分散式搜索引擎的DAO可能不会:你可以建立一个常规的搜索引擎,并使用Sci-Hub风格的技术来确保它的生存。

权力下放是可信的公平

有时,DAO的主要关注点不是需要抵抗民族国家,而是需要承担民族国家的一些职能。这通常涉及可以描述为“维护基本基础结构”的任务。由于政府监督DAO的能力较弱,因此DAO的结构需要具备更大的监督能力。这需要权力下放。

当然,实际上不可能完全消除信息和决策权的等级和不平等等等,但是如果我们能到达那里的30%呢?

考虑三个激励性的例子:算法稳定币,Kleros法院和乐观主义追溯性融资机制。

- 算法稳定币DAO是一种使用链上金融合约创建加密资产的系统,其价格跟踪一些稳定指数,通常但不一定是美元。

- Kleros是一个“分散的法院”:一个DAO,其职能是就仲裁问题做出裁决,例如“这个Github承诺是否对这个链上赏金的可接受的提交?

- 乐观主义的追溯性融资机制是乐观主义DAO的一个组成部分,该DAO追溯性地奖励为以太坊和乐观主义生态系统提供价值的项目。

在所有这三种情况下,都需要做出主观判断,这不能通过一段链上代码自动完成。在第一种情况下,目标只是获得一些价格指数的合理准确的测量结果。如果稳定币跟踪美元,那么您只需要ETH / USD价格。如果出现恶性通货膨胀或其他放弃美元的原因,稳定币DAO可能需要管理值得信赖的链上CPI计算。Kleros就是对提交给它的任何任意问题做出不可避免的主观判断,包括提交的问题是否应该因“不道德”而被拒绝。乐观主义的追溯性资金的任务是最开放的主观问题之一:哪些项目完成了对以太坊和乐观主义生态系统最有用的工作?

所有这三种情况都不可避免地需要“治理”,并且治理也非常强大。在所有情况下,治理是可攻击的,无论是从外部还是内部,都很容易导致非常大的问题。最后,治理不仅需要稳健,还需要可信地说服大量不受信任的公众,相信它是稳健的。

算法稳定币的致命弱点:神谕

算法稳定币依赖于预言机。为了使链上智能合约知道是将DAI的值定位到0.005 ETH还是0.0005 ETH,它需要一些机制来学习ETH / USD价格的(外部到链)信息。事实上,这个“预言机”是算法稳定币可以被攻击的主要场所。

这导致了一个安全难题:算法稳定币不能安全地持有更多的抵押品,因此不能发行比其投机性代币的市值更多的单位(例如。MKR,FLX...),因为如果是这样,那么购买一半的投机性代币,使用这些代币来控制预言机,并通过提供糟糕的预言机价值并清算它们来窃取用户的资金,这将是有利可图的。

以下是稳定币预言机的可能替代设计:添加一层间接寻址。引用 ethresear.ch 帖子:

我们建立了一个有13个“提供者”的合同;查询的答案是这些提供程序返回的答案的中位数。每周都有一次投票,Oracle令牌持有者可以替换其中一个提供商...

安全模型很简单:如果你信任投票机制,你可以信任预言机输出,除非7个提供者同时被破坏。如果您信任当前的 Oracle 提供程序集,则至少可以信任未来六周的输出,即使您完全不信任投票机制。因此,如果投票机制被破坏,任何依赖于预言机的应用程序的参与者都有时间有序退出。

请注意,该提案非常不像公司的性质。它涉及剥夺治理快速行动的能力,并故意将预言机责任分散到大量参与者中。这很有价值,原因有二。首先,它使外人更难攻击神谕,也更难让新的硬币持有者迅速接管神谕的控制权。其次,它使预言机参与者自己更难串通起来攻击系统。它还降低了oracle可提取价值,其中单个提供商可能会故意延迟发布以从清算中获利(在多提供商系统中,如果一个提供商不立即发布,其他提供商很快就会发布)。

克莱罗斯的公平

“去中心化法院”系统Kleros是以太坊生态系统中一个非常有价值和重要的基础设施:人性证明使用它,各种“智能合约错误保险”产品使用它,许多其他项目作为某种“最后的裁决”插入其中。

最近,公众一直担心该平台的决策是否公平。一些参与者已经提出了案例,试图从他们认为他们应得的分散式智能合约保险平台获得赔付。也许这些案例中最著名的是Mizu关于案例#1170的报告。这起案件从一起次要的语言争议演变成一个更广泛的丑闻,因为指控Kleros本身的内部人士正在协调努力,投掷大量代币,将决定推向他们想要的方向。一位辩论的参与者写道:

法院基于激励的决策过程...从表面上看,它被一个在法院中拥有非常大(25%)股份的开发人员所破坏。

当然,这只是更广泛辩论中一个问题的一个方面,Kleros社区应该弄清楚谁对谁错以及如何回应。但是,从这个个案的问题中缩小来,这里重要的是,像Kleros这样的东西的整个价值主张在多大程度上取决于它能够说服公众,它受到强烈保护,免受这种集中操纵。要让像克莱罗斯这样的东西被信任,似乎没有必要在高级法院中拥有25%股份的个人。无论是通过更广泛分布的代币供应,还是通过更多地使用非代币驱动的治理,更可信的去中心化治理形式可以帮助Kleros完全避免这种担忧。

乐观的复古资金

乐观主义的追溯性创始第1轮结果是通过24个“徽章持有者”中的二次投票选出的。第2轮可能会使用更多数量的徽章持有者,最终目标是转向一个更大的公民群体控制复古资金分配的系统,可能是通过一些涉及分类,小组委员会和/或授权的多层机制。

关于是否拥有更多公民还是更少公民,内部一直存在一些争论:“公民”是否真的意味着更接近“参议员”,一个深刻理解乐观主义生态系统的专家贡献者,它应该是给予任何积极参与乐观主义生态系统的人的职位,还是介于两者之间?我个人在这个问题上的立场一直是朝着更多公民的方向发展,通过第二层授权来解决治理效率低下的问题,而不是在治理协议中加入神圣的中心化。我职位的一个关键原因是内幕交易和自我交易问题的可能性。

乐观主义追溯性融资机制一直旨在与潜在的投机生态系统相结合:现在需要资金的公共产品项目可以出售“项目代币”,任何购买项目代币的人都有资格获得大规模的追溯资金补偿。但是,这种运作良好的机制主要取决于追溯性供资部分是否正常工作,并且非常容易受到追溯性供资机制腐败的影响。一些示例攻击:

- 如果某些人已经决定了他们将如何对某个项目进行投票,他们可以在发布决定之前购买(或者如果价格过高,则做空)其项目代币。

- 如果某些群体知道他们以后会对某个特定项目进行裁决,他们可以提前购买项目代币,然后故意投票支持它,即使该项目实际上并不值得资助。

- 资金决定者可以接受项目的贿赂。

通常有三种方法可以处理这些类型的腐败和内幕交易问题:

- 追溯性地惩罚恶意决策者。

- 主动过滤更高质量的决策程序。

- 添加更多决策程序。

企业界通常关注前两个问题,对第一次使用财务监督和明智的惩罚,对第二次进行面对面的访谈和背景调查。去中心化的世界对此类工具的访问较少:项目代币可能是匿名交易的,DAO对外部司法系统的求助充其量是有限的,项目的远程和在线性质以及对全球包容性的渴望使得对性格进行背景调查和非正式的面对面“气味测试”变得更加困难。因此,去中心化的世界需要更加重视第三种技术:将决策权分配给更多的决策者,这样每个决策者的权力就会减少,因此串通更有可能被举报和揭露。

DAO应该从公司治理或政治学中学到更多吗?

柯蒂斯·亚尔文(Curtis Yarvin),美国哲学家,他的主要“大想法”是公司比政府更有效和优化,所以我们应该通过让政府看起来更像公司来改善政府(例如,通过远离民主,更接近君主制),最近写了一篇文章,表达了他对如何设计DAO治理的想法。.毫不奇怪,他的回答涉及从传统公司的治理中借用思想。从他的介绍中:

相反,自工业革命开始以来,英美有限责任股份公司的基本设计大致保持不变——一位相反的历史学家可能会争辩说,工业革命实际上可能是一场企业革命。如果股份设计不是完全最优的,我们可以预期它几乎是最优的。

虽然这两种类型的组织之间存在明显的差异 - 我们可以称之为一级(主权)和二级(合同)组织 - 但似乎今年的社会有非常有效的二级组织,但不是非常有效的一级组织。

因此,我们可能更了解二级组织。因此,在设计DAO时,我们应该从公司治理开始,而不是政治学。

Yarvin的帖子在确定“一级”(主权)和“二级”(合同)组织之间的关键区别方面非常正确 - 事实上,这种确切的区别恰恰是我在上面关于可信公平的帖子中关于可信公平的部分的主题。然而,Yarvin的帖子立即犯了一个重大且令人惊讶的错误,他立即转向说公司治理是DAO应该如何运作的更好起点。这个错误令人惊讶,因为情况的逻辑似乎几乎直接暗示了完全相反的结论。由于DAO在其之上没有主权,并且经常明确地提供服务(如货币和仲裁),这些服务通常是为主权保留的,因此DAO可以学习的恰恰是主权的设计(政治学),而不是公司治理的设计。

值得称赞的是,Yarvin的帖子的第二部分确实提倡一种“沙漏”模型,该模型结合了分散的对齐和问责层以及集中式管理和执行层,但这已经承认DAO设计需要从一级组织中学习至少与二阶组织一样多。

主权国家效率低下,公司效率高昂,原因与数论可以证明很多东西,但抽象的群论可以证明的东西要少得多:公司失败得更少,成就更多,因为他们可以做出更多的假设,有更强大的工具可以使用。如果需要,公司可以依靠当地主权机构站出来捍卫他们,并提供一个他们可以依靠的外部法律体系来稳定他们的激励结构。另一方面,在主权国家中,最大的挑战通常是当激励结构受到攻击和/或面临完全崩溃的风险时该怎么办,没有外部利维坦随时准备支持它。

也许为主权国家设计成功治理体系的最大问题是萨莫·布尔贾(Samo Burja)所说的“继承问题”:当第一组人退休时,当系统从一群人管理过渡到另一群人时,如何确保连续性。Burja写道,公司往往根本无法解决问题:

硅谷热衷于“颠覆”,因为我们已经习惯了在公司等离散机构中仍未解决的继任问题。

DAO最终需要解决继任问题(事实上,鉴于加密早期采用者中“致富退休”模式的绝对频率,一些DAO已经必须处理继任问题)。君主制和类似企业的形式往往很难解决继承问题,因为制度结构与一个特定人的习惯紧密相连,要么被证明很难交出,要么存在一场非常高风险的斗争。像民主这样更分散的政治形式至少有一个关于平稳过渡如何发生的理论。因此,我认为,出于这个原因,DAO从更自由和民主的政治学派那里学到的东西比从公司治理中学到的要多得多。

当然,在某些情况下,DAO必须完成特定的复杂任务,并且使用类似公司的形式来完成这些任务可能是一个好主意。此外,DAO需要处理意想不到的不确定性。一个旨在围绕一组假设以稳定和不变的方式运作的系统,当面对这些情况的极端和意想不到的变化时,确实需要某种勇敢的领导者来协调响应。后者的一个典型例子是稳定币处理美元崩溃:当一个稳定币DAO围绕着它只是试图跟踪美元的假设而发展,突然面临一个美元不再是一个可行的东西的世界,需要快速切换到某种CPI时,会发生什么?

如果美元不再是可行的参考资产,RAI生态系统的内部经验的风格化图表正在经历一个意想不到的过渡到基于CPI的制度。

在这里,受公司治理启发的方法似乎更好,因为它们为应对这样的问题提供了一种现成的模式:创始人组织了一个支点。但事实证明,政治制度的历史也提供了一种非常适合这种情况的模式,并且涵盖了在危机结束时如何回到分散模式的问题:罗马共和国选举独裁者担任临时任期以应对危机的习俗。

实际上,我们可能只需要少量的DAO,这些DAO看起来更像是政治学的构造,而不是公司治理的东西。但这些才是真正重要的。稳定币不需要高效;它首先必须是稳定和分散的。分散的法院是类似的。一个将资金用于特定事业的系统 - 无论是乐观追溯资金,VitaDAO,UkraineDAO还是其他什么 - 正在为比利润最大化更复杂的目的进行优化,因此需要股东利润以外的对齐解决方案来确保它继续将资金用于预期的目的。

到目前为止,即使在加密世界中,也将成为“合同”二级组织,最终依靠这些一级巨头提供支持,对于这些组织来说,更简单和领导者驱动的强调敏捷性的治理形式往往有意义。但这不应该分散人们对这样一个事实的注意力,即如果没有一些非企业的分散形式来保持整个事情的稳定,生态系统将无法生存。